Bullshit Jobs Review

My entry for the ASX book review contest, reviewing David Graeber's Bullshit Jobs. I'd say it's still worth reading even if you haven't read the book.

“We must imagine Sisyphus wondering if he actually needs to bother.” Camus, probably.

“Man was born free, and everywhere he is in offices.” Rousseau, I’ve heard.

I. Are Many Jobs Pointless?

Famously some of the fiercest fighting during the Battle of Stalingrad took place in the city's tractor plant. I’m quite fascinated by those early soviet tractor plants (I promise this gets more interesting), mechanising agriculture represented a huge leap in productivity over pre-industrial farming.

If you were an older worker, or even a manger, at one of those factories and you remembered harvesting potatoes by hand, or you remembered the famines of the Tsarist and earlier Soviet periods, you’d have absolutely zero fucking doubts about what an immense contribution your work was making to society.

There must have been a tangible sense of mankind’s progress in those plants (I’ll move on before I get too sentimental about the Stalinist USSR.)

Reading about the Eastern Front, I can’t help feeling that if the battle of Stalingrad took place in modern Britain instead, we’d get stories about the valiant defence of a credit management office or a corporate law firm, or the storming of an investment bank.

I haven’t worked as a credit manager or a corporate lawyer, but I don’t get the impression that they typically feel as though their jobs are making a crucial contribution to the progress of mankind.

According to David Graeber’s book Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, many of them don’t feel they’re making any contribution to anything.

“In the year 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that, by century’s end, technology would have advanced sufficiently that countries like Great Britain or the United States would have achieved a fifteen-hour work week. There’s every reason to believe he was right. In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. And yet it didn’t happen. Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless. Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed.”

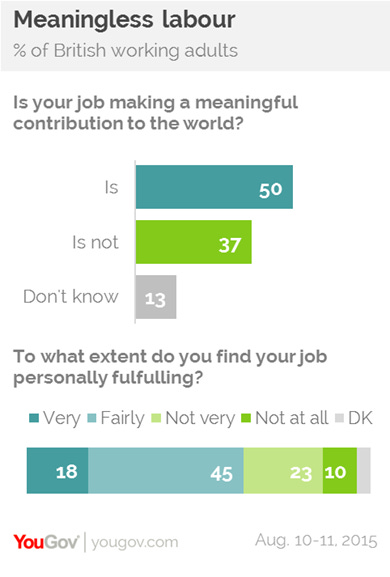

The book followed on from an essay Graeber wrote in 2013, arguing that “over half of societal work is pointless”, and a subsequent YouGov poll that found that 37% of Britons felt their jobs “didn’t contribute meaningfully to the world”.

It was a short run talking point in the press, and still gets mentioned in some circles, but it hasn’t had the lasting impact I feel it deserves.

If Greaber’s claim, that half of all our work is unnecessary, is true, it implies that we could roughly double GDP or double leisure time, or some combination of the two (adjusting for the marginal utility of labour), by eliminating BS jobs.there aren’t other many policy programs that, even theoretically, could potentially double everyone’s material quality of life.

If there’s any significant chance that Graeber is right, then BS jobs should probably be considered one of the biggest issues in 21st-century politics, and, so far they’ve gone mostly unacknowledged.

Scott Alexander made one short post on the subject, but it didn’t mention how much credence he gave Graeber’s claims; however, it was titled Bullshit Jobs (Part 1 of ∞), implying he had a lot more to say on the subject. That was in 2018 and so far the topic hasn’t appeared again on SSC or ACX since. And, sadly, Graeber himself has died since publishing Bullshit Jobs.

So, the original idea of BS jobs hasn’t been fleshed out much since its creation, and we have to rely on input from people who didn’t originate the idea and aren’t outside the normal human range of insightfulness. I’m hoping to contribute to that as part of this review.

II. Graeber’s Main Arguments and Evidence, and My Overview

To be upfront, I think BS jobs are real and pervasive, in Britain especially, and in a way that hasn’t always been the case; and even that Graeber might have underestimated the amount of BS work in the modern West.

Although I do have slightly mixed feelings about Bullshit Jobs (and Graeber’s work in general).

For one thing, I feel the book took an anthropological approach to a subject that really demands an economic one.

Graeber focusses a lot on the idea that doing BS work is more psychologically harmful than doing useful work, because BS jobs don’t provide “meaning” in the way useful jobs apparently do. So he argues that the net damages of BS jobs are even greater than the opportunity cost of having half the workforce doing nothing useful.

Graebe makes this psychological harm a central argument in the book, but I’m not convinced it deserves to be.

Perhaps as a public intellectual Graeber derived a lot of meaning from his work, but I doubt meaning is a major concern for the average toilet cleaner or plantation worker, and I think most work is psychologically unpleasant to some extent. If I’d written Bullshit Jobs, my main argument would have been “hey, we could have twice as much stuff or be working half as much.”

Graeber also doesn’t have much in the way of evidence to support his central thesis: that a lot of work in the modern world really serves no purpose, which is an incredibly bold claim to make mostly unsupported.

His main supporting data is the YouGov survey which found that “37% of British workers think their jobs are meaningless”.

Graeber was a Leftist in the Rousseau-ian tradition and the opposite of a misanthrope, he believed in the sound judgment and basic goodness of ordinary people, and emphasises repeatedly that he defines BS jobs to be “jobs considered useless by the people doing them”, and that the best way to know how prevalent BS jobs are is to ask the people actually doing them. Which provides us a clear metric to define BS jobs by and avoids upsetting anyone who thinks what they do really is valuable.

I’m sceptical that this is the right approach, and I’m not convinced this survey proves very much.

I doubt you can reliably expect people to know what contribution their work is making, and like most polls the responses could change significantly depending on how the question is phrased. “Make a meaningful contribution to the world” seems like it could be asking whether you think your job achieves something exception, like curing cancer, so might have a high rate of false negatives.

It’s not clear that responders necessarily think their jobs are economically useless in the specific sense Graeber wants to claim.

The Economist responded to the survey with a similar objection, suggesting that workers might not recognise the purpose their small roles cumulatively play in the grander scheme of today’s monopolies larger firms.

But, Graeber also argues that there are BS jobs that go unrecognised even to the people doing them (slightly contradictorily to his main approach to identifying BS). One hypothetical example he gives is a cleaner at a bank who thinks cleaning is useful, but if the bank itself is redundant, the cleaning is also indirectly redundant. So there’s a symmetrical counter argument to the Economists’ objection.

I think it’s also worth mentioning that jobs are one of the main status signals in our society, they’re things that can potentially make you rich or get you laid. It’s difficult to evaluate something you’re heavily invested in objectively and rationally.

It’s strange to accuse an anarchist of ignoring status, perhaps as a celebrated public intellectual it’s not something Graber considered that much. But the book really could have emphasised what a big… conflict of interest, I suppose, there is in asking people to evaluate the value of their own positions.

Overall, I think this poll adds some support to Graeber’s argument, but it’s far from unequivocal, and doesn’t shift my confidence in the claim that around 40% of work in the UK is unnecessary by very much.

III. Why Graeber Thinks There are Bullshit Jobs

That YouGov poll, along with anecdotal letters that Graeber’s received from people telling him about their BS jobs, are all the empirical evidence we get in Bullshit Jobs.

And I can’t say I’d expect any more.

If you stick to Graeber’s definition of BS jobs as “jobs that the person doing them thinks are unnecessary”, the only empirical investigation that’s possible is just to ask people “do you think your job is pointless?” There’s not much else you could investigate.

Without a concrete definition, it’s unclear what you should be measuring. And, since “what counts as a BS job?” is the question we’re trying to answer, there’s not much point using an ad hoc definition of BS either.

Since BS jobs are vaguely defined, and it’s contentious whether they even exist at all, there are inherent limits to the empirical approach. So the rest of the book attempts to provide theoretical reasons why we should think BS jobs are prevalent.

Graeber gives us five conceptual categories of BS work:

Flunkies only exist to satisfy the egos of people who like to be in charge of others. Examples include some receptionists, door attendants, etc. A lot of managers enjoy having, or are incentivised to have, a lot of underlings, often more than can be productively employed, in order to appear more important.

Goons do all kinds of zero sum competition games, like corporate lawyers who only make gains for their clients at the expense of rival firms, all kinds of advertising for already well-known types of product, lobbyists, public relations and I’m going to include anyone in education.

Duct tapers temporarily repair problems that should be fixed permanently, e.g. programmers managing bloated legacy code.

Box tickers fill out forms or publish psychology papers to create the illusion that something useful is being done, or avoid legal culpability. Lots of them in medicine, according to Graeber.

Taskmasters create unnecessary make-work for their underlings in order to appear more productive to their over-lings, e.g. middle management, any commissar beneath Stalin.

IV. Graeber’s Categories are OK

[If you’ve read Meditations on Moloch feel free to skip this part.]

The one category that really strikes me as true is the Goons, the foot soldiers in zero sum games (games where a player can only gain if another player loses, like gambling; as opposed to positive sum games where all players can benefit, like trade for example).

Graeber argues that the economic competition which capitalism relies on to ensure efficiency and foster innovation, can also lead to destructive competition where the efforts of both competitors cancel each other out, befitting no-one. And that therefore capitalist economies suffer from a lot of goon jobs.

The classic example of destructive competition is advertising, if one seller advertises they can gain extra sales, but if all sellers advertise it’s effectively the same as none of them advertising, because no brand stands out from the competition.

The Goons which Bullshit Jobs really excoriates are corporate lawyers (lawyers involved in resolving commercial disputes). Obviously courts can’t rule in favour of both sides of a dispute, so firms hire lawyers to advocate for their interests and, un-intentionally or deliberately, against the interests of their competitors, who are also hiring lawyers to do the opposite.

In both cases, the resources invested in advertising or legal representation cancel out and are effectively wasted.

Not that these jobs are always and completely pointless, some adverts point buyers to things they might not have known they wanted, and occasionally a corporate lawyer will help justice in its course, I’m sure.

But it’s easy to see how Don Draper, or a corporate lawyer with a broad perspective, would come to see their job as pointless; they’re only useful to their employer at the expense of someone else, and rarely do anything for society as a whole. If all firms could get together to organise a covenant promising not to hire anymore lawyers or do any more advertising, very little would be lost to anyone.

Graeber emphasises that these jobs can be lucrative for the individuals doing them, and create a clear example that being able to charge money for a service does not necessarily mean that the service is valuable to society as a whole.

How common Goon jobs are is a bit of a subjective matter, but some more examples of potential Goon jobs are: call centres, sales reps, public relations, recruitment, many types of consultant, cyber security, physical security, college admissions, anything fossil fuel related(?), immigration and border enforcement, paralegals, lobbyists, estate agents and (if you accept the signalling theory of education) the entire education sector.

In total, I think it’s fair to say that a sizeable number of jobs in modern Western economies could be considered Goon jobs.

Box Tickers and Task Master’s also seem very familiar to me. Essentially, they’re products of the kind of perverse incentives that public choice theorists complain often arise in government bureaucracies.

Whereas a private individual acts in their own self-interest and therefore has an incentive to make sure the task they’re doing is being done efficiently and is useful in the first place. Governments agencies are only accountable to voter’s wants filtered down through many layers of bureaucracy, which often leads to them only being accountable to some other government agency which itself has no incentive to ensure tasks are useful.

Which can lead to make-work schemes, and low rates of productivity that wouldn’t survive market competition.

Graeber does point out that the same phenomenon occurs in large corporations in the private sector as well though.

V. Graeber’s Categories Could be Better

Overall though, I don’t think anyone who likes economics is going to be that impressed with these categories, mostly they’re just examples of poor incentive structures and a couple don’t even look especially BS.

An apologist for flunkies could argue they’re serving a psychological want for their superiors.

Duct taping is perfectly reasonable in any situation that requires immediate returns.

You’ll get box tickers anywhere the boss of an enterprise doesn’t have perfect knowledge of what his employees are doing and can be fooled with the fake impression of doing work, i.e. the “principle agent problem”. Ditto with taskmasters.

Also, Graeber is an anarchists and heavily implies in the book that the epidemic of BS jobs is due to capitalism. But, even though he does document plenty of BS jobs in the private sector, most of his categories look like things that you’d get under any economic system.

The USSR was infamous for its box tickers and taskmasters, for example.

I’m not sure how he’d suggest getting rid of task Masters and box tickers other than just managing the economy better, somehow. Although I suppose anarchism suffers from the opposite problem of perverse incentives and probably wouldn’t have flunkies.

Admittedly, it’s hard to reject Graebers’ assessment that most Goon jobs exist because of capitalism. Goons arise when unrestrained competition creates coordination problems, which is basically capitalism sales pitch. Presumably there aren’t many telemarketers in Cuba or estate agents in North Korea.

I would have liked more nuance in Graeber’s theoretical categories, and even taken together, It seems unlikely that they could add up to nearly 40% of the workforce.

VI. Are there Better Ways to Explain Bullshit Jobs?

If Bullshit Jobs had been written by an economist it might have mentioned any economic theory whatsoever Adam Smith’s concept of “unproductive labour”. It’s one of the central theses of Wealth of Nations, but has largely been forgotten; the opposite of the famous invisible hand, that he barely mentions.

Smith has a kinda weird definition of “productive”; it’s anything funded by capital, as opposed to wages or rents, and it has to produce a lasting physical object.

So he really disapproves of servants, soldiers and anything to do with the church or aristocracy, but also professions like barbers and musicians (unless they record their performances, I guess, but he’s certainly not a fan of live music).

Famously, Smith also writes a lot about how currency is an illusionary form of wealth, and how Spanish gold hordes (the main form of currency in his time) were masking an unproductive real economy. He also rails against the waste of labour in gold mines.

I can understand why Smith considers some service sector jobs and landlords to be unproductive, but I’m not sure the Take That tribute act at your mums’ third wedding deserves the same indictment

I think,by unproductive, Smith mostly means “things that don’t contribute to the nations’ accumulated wealth”, not “things that don’t even serve a short lived purpose”, so it’s not quite the kind of “unproductive” we’re looking for. Although it does allude to some lack of real productivity in the services sector, that I’ll come back to later.

The insight that the means of exchanging value shouldn’t be confused with real value, and that it imposes a cost on the real economy seems like it might be relevant to the idea of BS jobs. But it’s not a well fleshed out theory in Wealth of Nations.

Building on Smith, Marx defines “unproductive labour” as [insert 3000 word definition about social relations, surplus-value, class society, modes of production, constant and variable capital, accumulation, dialectics, commodity production, M-C-M, exchange and use values, superstructures, materialism, and detailing all 12 possible interpretations]. The key insight though is that capitalism has transaction costs.

Capitalism is a decentralised system, with no central authority collecting information or assigning tasks. Economic actors rely on their own knowledge (explicit or implicit) to decide on which actions to take, organise their own work, and arrange transactions with other actors themselves. They also need ways to document and enforce those transactions.

All of this requires work. And it’s a lot of work. This is the category of BS work that explains why there’s a widespread perception that many jobs are BS, in my view, but it doesn’t feature in Graeber’s book.

Finding clients, buyers, sellers, employees and employers is a huge business occupying the labour of sales reps, product sourcing-ers, recruiters, human resources, half the internet, jobs boards etc.

Accountants obviously deal with the accounts you need to have an economy with circulating money.

We’ve mentioned that corporate law involves an element of zero-sum competition between the lawyers themselves, but even if corporate law was nationalised and corporate lawyers all pursued a common goal (justice you’d hope), it would still be the case that they’re only required in the first place to arbitrate disputes between competing firms, in a way that’s still zero-sum. They’re still Moloch’s creations.

The portion of the stock market not devoted to speculation aggregates knowledge to direct investment. Investment banks connect venture capital to entrepreneurs.

The estate agent we accused of doing BS work earlier might object:

“Yeah, I’m paid to inflate the price of a house which is good for the seller but equally bad for the buyer. But people need to be able to buy and sell houses, I facilitate that, so my job’s only 50% BS.”

But people only need to buy and sell houses if there actually is a housing market.

There’s a whole class of jobs devoted to policing who can and can’t access things with no marginal cost of production that could in theory be distributed freely, like Netflix does with viewing for films, and a part SubStack’s team do with blogs.

Marx’s central argument is that organising work around capitalist institutions creates lots of second order work in running those institutions.

I can’t think of a catchy name for “work that’s only necessary if you live in a market economy”, maybe “changing” or “changers” after the money changers Jesus threw out of a temple. But I think this is the major theoretical discussion missing from Bullshit Jobs. “How much work do we need to do so we can do the actual work that needs doing?”

Marx isn’t suggesting you could remove these jobs entirely without causing harm, like you probably could for most of what Graeber considers BS work. Obviously getting rid of accountants and corporate law tomorrow would cause anarchy.

Any economy needs organisation and these jobs provide that. But they provide it in a way specific to a certain mode of production, Marx’s argument is that other modes of production might be able to provide organisation more efficiently. i.e. that these jobs might only look productive in the near view.

Looking at planned economies, these kinds of jobs don’t exist and their equivalents in the central-bureaucracy employ fewer people.

At its height, the Soviet planning Bureau, Gosplan, had a staff of just a few thousand bureaucrats, for an economy of almost 300 million people, for example. And those bureaucrats were only equipped with abacuses.

Obviously, Soviet bureaucracy was more extensive than just its planning office, but it’s hard to deny the centralised nature of the USSR’s economy provided economies of scale when it came to organisation and information processing tasks. It’s most apparent in the skylines of Soviet cities and their Western counterparts, typically the former was dominated by factory chimneys, whereas New York and London are almost entirely high rise offices.

I’m not sure how Graber would have suggested the organisation provided by changing be provided under anarchism (people power? bickering middle aged people in local councils maybe?), the topic as whole is conspicuously absent from the book. Although, if you view establishing central planning as a long term technical problem, you could argue changing is a form of duct taping, I suppose.

Marx doesn’t emphasis changing as one of the major drawbacks of capitalism, even by attributing the idea to him, I’m reading quite a lot into his work which might not be there. That might be because changing was a much smaller fraction of the total economy in the 19th-century.

In the 21st-century, and in Britain especially, changing is increasingly becoming most of the economy.

VII. Changing Jobs are Growing in Number

In a chapter on Rusia’s transition to capitalism, The Commanding Heights, a book about 20th-century economic history jokes:

“Private property can exist only within a framework of contracts and laws, and the [Russian State Committee on the Management of State Property] ran up against a problem that would astonish people in a country like the United States—an acute shortage of lawyers.”

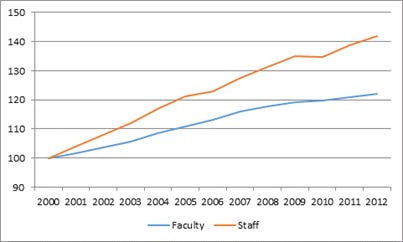

Growth of US lawyers:

Commanding Heights also had a section about China developing a marketing sector after Deng Xiaoping’s reforms.

Leaked footage from inside the growing British marketing sector:

As well as in ex-communist countries, employment in changing jobs has also grown in the never-comunist-but-increasingly-market-oriented-since-the-70s-countires. When Britain or the US get referred to as having become service economies, most of those new service jobs are forms of changing.

Outside the UK, the cost of changing is perhaps most obvious in US healthcare. Measuring its performance by life expectancy, private healthcare in America provides a slightly worse service than the more planned systems in Europe, and at 4x the per-capita cost!

You can make excuses for US healthcare like “it funds research”, “Americans have less healthy lifestyles” and “the wealthy pay for expensive but low cost treatments, whereas public healthcare allocates treatment in a way that optimises the population life expectancy.” All true, but 4x is a truly immense cost disparity that can’t all be explained circumstantially.

Possibly a large part of the disparity is because US healthcare involves large numbers of workers not directly involved in providing healthcare.

For the UK’s public healthcare system, Gov.uk claims “The UK spends only around 2% of healthcare expenditure on administration” and “Only around 3% of NHS staff are non-clinical managers”. I can’t find figures for American healthcare, because it’s all spread out over lots of organisations, but I highly doubt the entire insurance industry, malpractice legal departments, pharmacological reps selling drugs to doctors, departments devoted to managing hospital’s finances etc. make up less than ~3% of US healthcare spending.

Overall the market system looks much more bureaucratic than the more planned European equivalents, only it’s replaced managers with changers.

If you think the UK has a housing market that’s comparably dysfunctional to the US healthcare market, well, there’s also a correspondingly large number of British changers working at selling, appraising and financing houses.

In the last few decades British universities have transitioned from a more public model to a more private one, subsequently there has been an explosion of administration on campuses.

There’s also large sections of the financial sector that serve dubious purposes.

When banks issue home loans, for example, it has the effect of shifting the demand curve up, raising prices and forcing the marginal un-leveraged buyers to also take out a loan to reach the now higher prices, leading to higher prices and more debt, etc. etc., in a cycle that only benefits lenders.

Since around the 1970s, the proportion of jobs in the service sector has grown rapidly and come to make up most of the economy in many Western countries.

I don’t think Graeber would argue that every service sector job is BS, perhaps not even most of them, but there’s a stronger case to be made that the average service sector job is more BS than the average manufacturing one. And probably this growth in what’s effectively private sector bureaucracy has contributed to the perception that many jobs are BS.

If you count private sector bureaucrats, there’s a strong argument to be made that Britain has become the most bureaucratic society in history over the last few decades, and the rest of the Western World isn’t far behind.

Jobs that fall under Marx’s category of unproductive labour are less obviously pointless than the categories of BS jobs that Graeber offers, because a certain number of them are necessary . But it’s not clear that the expansion of these jobs is adding any new value.

Capitalism is a profit maximising system not a welfare optimising one, it always looks for new forms of profit and it’s not necessarily true that all of them will be welfare improving, over time perhaps you should expect the proportion of profitable-but-not-welfare-improving jobs to rise.

And, since changing jobs have come to make up an increasingly large proportion of our economies, even if only a (maybe largish) fraction of them are genuinely BS, they still make up a large number of BS in absolute terms.

I’ve focussed on the Marxist concept of unproductive labour here, only because I think it provides the clearest way of thinking about why these jobs might be non-productive. But, I think you can still entertain the idea of changers even if you don’t accept the Marxist framing. Thinkers from other schools of thought have also noticed a similar trend.

Tyler Cowen suggests that in recent decades Western economies have suffered from a “Great Stagnation”, where, despite positive GDP trends, real consumption has leveled off, and we’re really much poorer than the numbers suggest. And he attributes that disparity in part to a rise in economic activity less value has been created, particularly finance and government spending.

VIII. Another Type of Bullshit Jobs I think Graeber Misses

Another category of BS work I think Graeber misses is something I think of as “rickshaw-ing”.

Rickshaws are a form of transport where one person pulls another person sitting in a chair on wheels, they were especially prevalent in East Asia prior to industrialisation.

They’re operated by one worker, transport one passenger and move at walking or running speed (i.e. the speed of the guy pulling, i.e. the same speed people move at without transport). Basically you pay someone else to walk for you.

In his travel diaries, Einstein mentions reluctantly hiring a rickshaw and feeling “loathed to use a human being in this way.”

Unlike say a train, there’s no improvement in speed and no gains from a division of labour, train passengers couldn’t travel faster if they tried to transport themselves (i.e. walking) and one train driver can transport many passengers.

From a societal point of view rickshaws are useless because people could get around just as quickly, and using half the man-hours, if they just did the work of moving themselves, i.e. got out and walked. (Yes, an athletic rickshaw puller transporting a cripple whose time is very valuable is a real comparative advantage, but the portion of rickshaw-ing work that involves moving people who could have moved themselves almost as easily is BS)

Thankfully rickshaws are out of fashion in the modern West, but there are still many jobs in this category of providing-services-that-customers-could-just-as-easily-provide-themselves. Domestic cleaners, maids, private cooks, all forms of servants, waiters (restaurants are outsourced versions of private cooks and servants to some degree), all provide little net gain to society as a whole. Taxi and Uber drivers are also a bit rickshaw-ish, as well as sex-workers.

Whenever a parcel gets delivered I wonder if the proliferation of delivery drivers and home food deliveries, over the last decade, represents a real gain in economic efficiency over just … I don’t know… walking somewhere to collect things, or if it’s another by-product of rising inequality. Since delivery drivers aren’t paid well and seem to have poor working conditions, I’m inclined to think they’re a kind of rickshawing.

Because these jobs involve one person selling their labour to provide someone else with convenience with little comparative advantage, they’ll be more common the more unequal a society is. Which means they’re another type of BS work that expands the more market oriented an economy is. I can’t find any data on the prevalence of these jobs over time, but anecdotally it seems that it’s become common for many white-collar city dwellers to regularly eating out at restaurants and even hire house cleaners, in a way that it logically can’t be possible for most people.

IX. Can We Reduce the Number of Bullshit Jobs?

When Graeber explains why he thinks BS jobs exist, even though in theory market completion should weed out unproductive work, he often blames the social expectation that people should have jobs, and refers to Protestantism and the Protestant Work Ethic a lot.

He even goes so far as to claim that many workplaces are insulated from market forces and that the relationships between people in corporations is more similar to vassal relations between lords and serfs than buyers and sellers, in that they from a hierarchy that’s more straightforwardly social rather than economic, something Graeber terms “managerial feudalism”.

“[C]orporations are less and less about making, building, fixing, or maintaining things and more and more about political processes of appropriating, distributing, and allocating money and resources.”

“Under classic capitalist conditions of this sort it does indeed make no sense to hire unnecessary workers. Maximizing profits means paying the least number of workers the least amount of money possible; in a very competitive market, those who hire unnecessary workers are not likely to survive. Of course, this is why doctrinaire libertarians, or, for that matter, orthodox Marxists, will always insist that our economy can’t really be riddled with bullshit jobs; that all this must be some sort of illusion. But by a feudal logic, where economic and political considerations overlap, the same behavior makes perfect sense.”

Managerial feudalism seems like slightly too vague a concept to be any use in informing policy choices. I think Graeber’s anti-feudalism reforms would have just been anarchism.

He also suggests universal basic income as a solution, but it’s not clear to me why that would reduce the number of BS jobs any more than it would just reduce the number of all jobs.

Hopefully I’ve presented some more concrete potential explanations for BS jobs grounded in standard economic concepts like perverse incentives, principle agent problems, market failures, information asymmetries, transaction costs, rent seeking and public choice theory.

Even so, I’m not sure I have anything that useful to suggest based on that.

In our 21st-century, more market oriented, economies, whilst it’s certainly true that government programs can, and do, create BS jobs, I agree with Graeber that it’s mainly the private sector, and particularly the service sector bureaucracy, that is fuelling the current growth in BS jobs.

One obvious remedy would just be to move more of the economy under government management. Reducing the size of the private sector would reduce the number of goons, changers and rickshawers.

But it seems like expanding the public sector could easily create an equal number of task masters, box tickers and duct tapers.

Maybe a planned economy, managed by hyper-competent public servants deeply versed in the teachings of public choice theory? Or market without market failures or a means of exchange? If that’s not too much to ask.

One tantalizing possibility is that,if you accept that BS are predominantly in the service sector, they’re disproportionately vulnerable to automation by AI.

You could imagine a strange future where large numbers of jobs are still pointless, but it doesn’t really matter since they’re being performed at minimal cost.

A more worrying possibility is that, if BS jobs are widespread it implies that it’s difficult to curb the growth of pointless work, and the labour freed up by automation might just end up in make-work schemes.

X. Final Thoughts

I’ve been quite critical of Graeber, but I do think he’s written an important book.

I wouldn’t say Graeber really broadened my understanding of why some jobs are BS, and he doesn’t do a good job proving that many jobs are pointless, but he’s certainly opened my mind to the possibility.

I think about “bullshit jobs”, the phrase he coined, all the time in my personal life. In fact, I don’t think anyone I know works an un-ambiguously useful job, and I notice jobs that look suspiciously BS all the time.. Partly that’s just being an anti-social hermit, and partly it’s probably being from the kind of background that changers usually come from, but bullshit jobs seem very real in my experience.

If a time traveler from the future was writing a book about life in 21st century Britain and asked me what I thought the key elements were/are, I’d say: “You have to understand what bullshit jobs are, but don’t bother reading Bullshit Jobs. Also, please take me with you.”

A (slightly fictionalised version for anonymities sake) of my own job history goes: competing for credentials in the education system, serving cups of tea at a café, doing the coding for fruit machines and a start-up automating parts of the legal process for selling houses.

I hope people enjoyed those cups of tea, because I’m nearing thirty and it’s the one clearly worthwhile thing I’ve done so far.

Before Bullshit Jobs, another book that changed my perception of my surroundings by a lot was Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education. Which argued that the most of the extra life-time-income you earn from completing school was due to a zero-sum signalling process, not from accumulating skills or knowledge, and that, at a societal level, most of the apparent benefits of education are illusory.

The whole purpose of, at the time the main thing I’d been doing in life, education, completely withered under the light of a bit of economic theory.

In a way, Bullshit Jobs is the more general version of The Case Against Education. But, while The Case Against Education has a much narrower scope, it nails a convincing theoretical explanation, and backs it up empirically, in a way Bullshit Jobs just doesn’t.

Personally, I think it’s likely that BS jobs are a real and a widespread phenomena like Graeber claims. And, hopefully I’ve provided some extra theoretical grounding for the idea, but it’ll take a much more rigorous book/book-review to convince any sceptics.

I think there’s a big opportunity for someone to write a book arguing that a large number of jobs are pointless more persuasively than Bullshit Jobs manages. And maybe gives the idea a more respectable name. But it’d need to be an incredibly ambitious book given the scope of the claim.

I wish bullshit jobs were more widely discussed, and think they should be a major consideration in comparing different economic systems and policies. But that’s difficult when they’re so nebulous.

I can accept that the 40 hour work week was part of the Faustian pact that allowed humanity to live indoors and past the age of 36. But I still find Bullshit Jobs implication, that it’s not easy to reduce the total time people spend working, quite discouraging. Even with consistent technological growth, a future full of pointless make-work looks entirely possible, maybe even likely.

Hopefully Keynes’ great-grandchildren can look forward to their promised 15 hour work-week.

I quite liked this review, kept my interest throughout and I'm probably going to keep thinking about it and read some more books as a follow-up since I think your overall point that this idea is important and under-discussed is true. That's pretty much my criterion for a successful piece of writing, so I think you've succeeded.

The humor was good. I didn't laugh at everything, but did laugh out loud at the "any economic theory whatsoever." I think if anything more space between jokes would help, since they fell a little flatter when closely sequenced together.

I'm convinced that the kind of bullshit jobs you talk about are indeed real and very frustrating. I read the first parts of the book years ago and I remember being confused if Graeber thought the jobs were inherently unproductive and could be eliminated or if they are unproductive consequences of a complex system. I thought Graeber was arguing the former and I see you as arguing the latter, which I find to be defensible and compelling, so overall I think I was convinced that you understood Graeber better.

I think sections IV and V are very strong in this format and I was very convinced you were improving on Graeber's ideas. The basic arguments about planned economies having less of this stuff were surprising and gripping and I'm going to keep thinking about them. The section on rickshawing was also excellent, and a great term for something I've wondered about.

I have worked jobs that meet Graeber's definition, and especially what strikes me is just how murky the actual purpose of so many jobs is. Technological development for example can have real effects on people's lives and economic productivity, but can also be used as a tool in zero-sum budget fights within large semi-feudal organizations. But to win budget fights with technology, one needs to pretend that the technology is going to have a real effect. Most people seem fine with it, but I find it to be quite difficult. It seems clear to me that the stated purpose of a job and what the job actually achieves are extremely far apart, but most people weirdly don't seem to mind? The post-2007 trend of large corporations justifying themselves to their employees with social impact buzz words like sustainability and diversity seems to me deeply personally unsatisfying, because clearly these things are not the actual priorities of large corporations, compared to an old school Adam Smith/Wall Street "seeking profit is to the benefit of all" but I may be wrong there. One thing I'd like to look more into after your review is the Marxist and post-Marxist theory of alienated labor which feels relevant and might be due for a rehabilitation away from post-structuralist humanities academia.

I imagine that the political angle would be alienating for some, but I was fine with it and felt this was an inherently political topic. All claims were justified and seemed to be coming from a place of knowledge and openness.

Hope this helps, great stuff.

Okay, this was a cool review that really changed my perception of the bullshit jobs idea, which I had previously dismissed (I started this review looking forward to you tearing it a new one!) Thank you for knocking down my unearned confidence.