Only the Dead at Dawn (Part1/2)

A big-picture, Malthusian view of human history focusing on war and conflict over resources.

[If you want some background music]

“Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going? Is everything fighting monkeys?” –Gauguin, probably.

Jane Goodall was shocked to discover that chimpanzees fight wars. I don’t know much about Goodall’s worldview, but if it was one that emphasised the fundamental goodness of humanity or the benevolence of the universe, her discovery must have shaken those presuppositions.

The “Chimp-wars-shows-how-evil-humanity-is-by-nature” view is a common interpretation of Goodall’s findings, I don’t think the full significance of that discovery has been realised.

The fact that our nearest relatives are among only a handful of species that wage war should have enormous implications for our understanding of human evolution and the early development of human societies. It means war is likely extremely ancient and uniquely consequential in human evolution.

War is one of the defining characteristics of humanity, if not the defining characteristic. Every other aspect of human history and psychology should be considered in that light.

I’d like to offer a broad overview of our origins, one with war as a central pillar.

This is a perspective from an (at best) amateur anthropologist, but that needn’t necessarily be entirely for the worse. Academic anthropology tends to shy away from Grand Theory, and disfavours theories with unpleasant implications, I feel.

It’s also a view that provides a very fundamental way of thinking about history, and what the pre-industrial world was like at its most basic level (it’s also sort of become the foundation of my worldview), if it’s convincing you’ll never view the past in quite the same way. But I’ll warn you, it’s not a pleasant view.

[This isn’t the first essay I’ve written but it’s not the most recent either. I thought I’d make this the first post on the blog since this view of human history colours so many of the other topics I’d like to cover. Apologies if the writing’s a bit amateurish.]

I. Malthus and Moloch

[Everyone knows what Malthusianism is, so I’ll keep it short.]

Goodall might have been surprised, but from a Malthusian perspective it’s hard to imagine how chimps could not fight wars.

Malthusianism has been through an unfashionable phase in academia over the last few decades (I genuinely think just because it’s unpleasant and has been used to justify several genocides some questionable policy choices), but to me the logic seems inescapable. The main “goal” of reproducing organisms is to, well… reproduce. Which means populations will grow, until they reach a constraint and the marginal organism can’t reproduce anymore. Usually the constraint is a bottleneck in resources. Without constraints populations would grow to infinity, there aren’t infinitely many of any organisms, so we can be sure all populations of organism are growing or are bound by a constraint.

For chimps, that constraint is the finite number of fruit trees they rely on for food (modern chimp populations probably are growing because poaching has depressed their numbers, we’re mainly focussing on the evolutionary history of chimps here).

Chimps need food to survive, there’re a finite number of food sources, and population growth guarantees a shortage. Necessarily the system reaches a point where excess chimps starve and the population stabilises. The only way a chimp can ensure a food supply is to prevent other chimps taking it. Since the fruit trees can’t be hidden or locked away, chimps have to resort to threats or violence.

So mystery solved then. Chimps fight each other for the same reason all organisms fight each other, they’re all caught in the same Malthusian trap. Goodall should have predicted chimps would fight wars if she’d just have bothered to study any other organisms that reproduce and need resources. Any organism whatsoever.

Except, most animals don’t fight members of their own species. A lot of animals don’t even have the capability to kill a member of their own species, and predators don’t typically fight each other if they can avoid it.

It seems like Malthusian theory predicts war should be very common, but it was big news when researchers found any examples of it at all, beside humans.

Malthusianism looks logically watertight, and it’s the basis for the theory of natural selection, so it’s a bit of a puzzle exactly why apparently only chimps and humans follow it through to its logical endpoint.

II. Coalitions

Fighting another member of your own species is extremely risky, they’re typically about as powerful as you are. If two equally large tigers come into conflict they both take a significant risk of death or injury. Even if one tiger is much larger, they might be guaranteed to win, but there’s still a risk of injury, which might still prove fatal. Any fight between individuals, even individuals with a large mismatch in power, comes with huge risks, especially if you rely on a healthy body to support yourself and you’re British don’t have healthcare. The potential rewards for that kind of fighting usually aren’t worth the risks, which is why solitary animals rarely fight each other.

If a group of animals attack a solitary member of their species however, they can often dispatch the loner at minimal risk to themselves.

Fighting as a group has immense advantages. You can attack from several angles simultaneously, aiming at unguarded spots, you can disable the enemy with overwhelming force before they have a chance to retaliate, if a member of your groups is at risk they can retreat while the other members cover them, part of your team can focus on disabling the enemies weapons or defences while the rest attack them in a vulnerable, defenceless state, members of the group can mutually cover each other weak spots etc.

Several animals acting as a group is usually much deadlier than an equal number of animals acting individually and much stronger than a single lone animal.

So do chimps fight as a group?

In The Goodness Paradox Richard Wrangham describes the typical tactics used in chimpanzee warfare:

“Goodall (1986) summarizes the observations as follows: the attacks lasted at least 10 min each; the victim was always held to the ground by one or more of the assailants while others attacked; the victim was dragged in at least two directions, eventually gave up resisting, and was essentially immobilized by the end of the attack.”

Note that the victim is a solitary chimp against many attackers, and that it takes a full 10 minutes to dispatch them. The victim could inflict serious harm to the attackers in that time, if they weren’t restrained, and they couldn’t be restrained without overwhelming numerical superiority.

Wrangham then mentions that groups of males would go on silent raids into rival territories, aiming to assassinate lone chimps from the rival group.

They would also spend time patrolling the borders of their territory on the lookout for enemy raids. If they did detect an enemy raid the two sides facing off would both have several adult males, so neither side would hold enough of an advantage to attack without risk, so usually the raiders would just leave. There’s no pitched battle.

The cases where a lone chimp will attack another lone chimp are when the mismatch in power is overwhelming, like an adult male vs an infant for example (infanticide of infants from rival groups was one of the earliest discoveries of homicide in chimps).

Basically chimps will kill outgroup members whenever they have the chance to do it safely (except sometimes females, you can probably guess why).

Incidentally, the reason chimps don’t just huddle together for protection all the time is because they need to disperse to forage.

You can imagine that chimps (and our ancestors) likely evolved to live in troupes because of the advantage it gave in securing resources (or they already lived in troupes, which were then moulded into becoming more coalition-ary. For example Gorilla troupes are dominated by one silver back, so can’t form male coalitions).

Once all chimps started forming coalitions however, that advantage was nullified, as pitched battles between two coalitions was too dangerous. A constant low level guerrilla war broke out, each group raiding and ambushing lone members of rival groups to whittle down their numbers, weaken them, and eventually gain control of their territory; a guerrilla war stretching back millions of years, generation after generation,.

Wolves and lions also engage in similar coalition-based violence (war), using similar exclusively-many-vs-one tactics.

It seems any animal with a capacity for violence, and that also forms coalitions (not just herds or harems etc.), will face evolutionary pressures to develop instincts to kill outgroup members, and end up in this kind of low-intensity guerrilla war.

Once conflict had been established, the pressures to kill out-group members only intensified as now rival groups posed a threat beyond just competing for food; a security threat. Eliminating enemies before they eliminate you, or before they grew too strong, became paramount to survival. An example of the prisoner’s dilemma, or security trap. He who strikes first often strikes last.

Chimps breed slowly and live at low population densities, so naturally mortality of any kind is a rare event. Therefore actual killings in war must also be rare ( < chimp lifespan*number of chimps). It’s probably why chimpanzee warfare went unnoticed for so long before Goodall in 1974.

In an abstract way though, war is the central fact of chimpanzee existence.

Membership of a coalition, and the success of that coalition in war, is the primary factor affecting reproductive fitness for (male) chimps.

Malthusian explanations of war are pretty old, but without the insight into the limits of individual violence and how coalitions overcome that constraint on violence, you can’t weave a coherent theory about why war isn’t everywhere.

Here’s the original paper outlining that interpretation of chimpanzee war.

I’ll claim this is the fundamental cause of war, Malthusian pressures vented through coalitionary violence; that we should expect war to have a history that stretches back much further than humanity itself (at least to our common ancestor with chimps), and that war will persist as long as groups compete over finite resources.

III. Dawn of Man

Having realised how central warfare is to chimpanzee life (because of coalitions), can we speculate about human evolution in that light?

Well, war is just as universal among human societies as it is among chimpanzee troupes. From War Before Civilisation:

“In one sample of fifty societies, only five were found to have engaged “infrequently or never” in any type of offensive or defensive warfare.1 Four of these groups had recently been driven by warfare into isolated refuges, and this isolation protected them from further conflict. Such groups might more accurately be classified as defeated refugees than as pacifists.”

The evidence strongly suggests that war is a normal part of life for nearly all hunter gatherer groups.

One of the world’s last reaming uncontacted tribes, on North Sentinel Island, is famous for the swift brutality it dispatches visitors to the island with. Wikipedia cites this as evidence for the “islanders' desire to be left alone”. As if they held a council and decided to stay isolated from civilisation.

Maybe a charismatic islander pleaded something like “Antibiotics and a double digit life expectancy might seem tempting but of course we need to be cautious of the spiritual malaise civilisation brings.” And the others agreed. ”Yes, and let’s not forget our unique position in the wider narrative structure of human history either.”

But of course, killing outsiders is the default choice for hunter gatherers.

North Sentinel Island is only about 4x4 miles in area. The pigs and turtles that islanders rely on for food must grow scarce with regular frequency, probably the whole island erupts in civil war every few years when people grow hungry. Under those conditions they’ll “desire to be left alone” by anybody who needs to eat, other islanders included.

Typically, when interviewed, hunter-gatherers will claim vengeance or correcting some injustice as their motivation for persecuting war, rather than a desire for more territory or resources, although War in Human Civilisation notes that territory does usually change hands.

Obviously there’s a strong social desirability bias against admitting “Yeah, I committed genocide for material gain.”

But it might still be the case that vengeance is the most common proximate cause of violence. Humans do have a strong instinctual urge for vengeance, whereas it seems most other animals don’t.

Homicidal vengeance isn’t an instinct that gets triggered often in modern people. If you’d like to get a sense for what it feels like, imagine humiliating your worst enemy, who also happens to embody the fear of death, getting him deported, then banging his wife and taking his house. Or alternatively, contemplate that the portion of your life’s earnings you’ve paid in rent would have been enough to get on the property ladder by now. From that perspective it easy to see the subjective motivations hunter-gatherers have to kill.

Since vengeance doesn’t actually correct the harm done to you (it only spreads more harm), it’s not an obviously logical response to wrongdoing (except maybe in some repeating game-theory situations). You have to wonder why we have this instinct in the first place.

Probably the instinct for vengeance is an evolutionary legacy of the long history of Malthusian struggle.

But it still true that hunter gatherers often proactively “hunt” members of rival tribes without provocation, the same way chimps will.

In War in Human Civilisation (excellent book btw, but you have to drink every time he mention the “red queen effect”) Azar Gat confirms that hunter gatherers also follow the only-fight-when-it’s-completely-safe strategic logic. Which typically involves several attackers ambushing lone individuals.

In fact participation in war is usually completely voluntary for hunter gatherers. Males aren’t required to fight, like modern conscripts are. They’ll only fight if they personally feel like it, for reasons like capturing women, gaining status, or just for fun. I imagine there are social pressures, but it really highlights how this kind of warfare is beneficial to individuals, and not the product of group selection.

Hunter gatherer war looks a lot like chimp war, except that the more lethal weapons, and especially ranged weapons, provide more types of opportunities to only-fight-when-it’s-completely-safe.

Being able to kill very quickly, and having the element of surprise, lets you disable even moderately large groups of enemies before they can strike back. So there’s still lots of raiding and ambushing isolated enemies, but there’s also night-time raids on whole villages and other ambushes against large-ish groups of enemies. Strategies chimpanzees would rarely attempt.

That means humans can take advantage of very large group sizes, in a way chimps can’t.

Remember chimps almost never attack multiple defenders, being in a group is useful to chimps up to the point of overwhelming numerical superiority against a single opponent, and redundant beyond that.

Even having overwhelming numerical superiority against two enemies often isn’t worth it, because even just two enemies have many of the advantages of a group (covering each other’s backs etc.) which makes them a much riskier proposition than two lone enemies.

Chimp troupes will split beyond a certain size and the two factions will start warring (this is what Goodall observed in Gombe). The chimp Dunbar number is much lower.

I’m not certain the limit on chimp troupe size isn’t due to the maximum size of territory that can be patrolled, or brains that are too small to socialise enough (baboon seem to manage), or available food, or whatever, but this tactical reason seems like the most likely explanation to me, the others all seem to have fatal weaknesses (which I’ll discuss in the comments if anyone’s interested).

Humans have a much higher maximum-number-of-enemies-it’s-worth-attacking, because of the lethality of our weapons, provided our own group size is big enough. Ten human raiders can dispatch ten enemies if they catch them sleeping, or without their weapons, for example. Chimps don’t have the lethality to kill a sleeping opponent before he wakes up and starts fighting back.

Humans have especially large group sizes (~150, i.e. Dunbar’s number), compared to most primates. Which is usually explained by our large brains, and large brains might be necessary to facilitate large groups, but I think this military advantage is the fundamental reason.

Another feature of human evolution that’s less mysterious in this paradigm is bipedalism.

Widely considered the first major adaptation in human evolution, it happened shortly after the split between the ancestors of chimps and humans.

But running and walking on two legs, instead of four, is really slow and unstable. Since running and walking are the main functions of legs, it’s always been a mystery why we would evolve away from normal quadrupedalism and towards bipedalism, especially considering the intermediary form must have been extremely awkward.

Most explanations revolve around freeing up the hands. Other primates still have dexterous hands but can’t use them and walk at the same time, so any hands-based explanation needs to postulate a task that requires simultaneous hand-use and walking, one that was important enough to offset the substantial disadvantages of bipedalism.

Usually anthropologists suggest things like carrying food or infants. That might be true, but if you accept war as the primary selection pressure on chimps, and therefore probably also on human ancestors, one activity that really benefits from holding things, while still staying mobile, is wielding weapons.

Bipedalism is slow over any distance (even really long distances, apologies to any persistence hunters) but it makes you agile.

If a horse wants to move backwards, or to the side, it has to awkwardly coordinate four feet or turn its whole body around, its body is about 8 feet long so it’s really slow. Standing up, a human body is effectively about half a foot long, back to front, so we can spin around really fast. Our legs don’t tangle with each other or need to move in a complicated sequence, so we can jump sideways, or backwards, pretty nimbly.

If you’ve ever fenced, or done any martial art that focuses on striking, you’ll know that sort of agility is extremely useful, dodging and keeping distance (footwork) is the main way you avoid the opponent’s weapon. A centaur might be fast in a straight line, but they’d be terrible in a duel or skirmish.

Probably bipedalism was later co-opted for different functions, but, to me, this looks like a plausible story about its origins.

IV. Agriculture

We’ve painted a picture of the pre-agricultural world that strongly resembles the world chimps, lions and wolves live in now.

War is endemic, overpopulation is resolved through killing, anywhere virgin land is abundant is soon overrun by population growth, even where there is enough land people’s evolved instinct to hunt strangers ensures violence happens anyway.

People live bound to the territory they can defend and are walled in by other hostile groups defending their own patches, they starve if that territory isn’t rich enough.

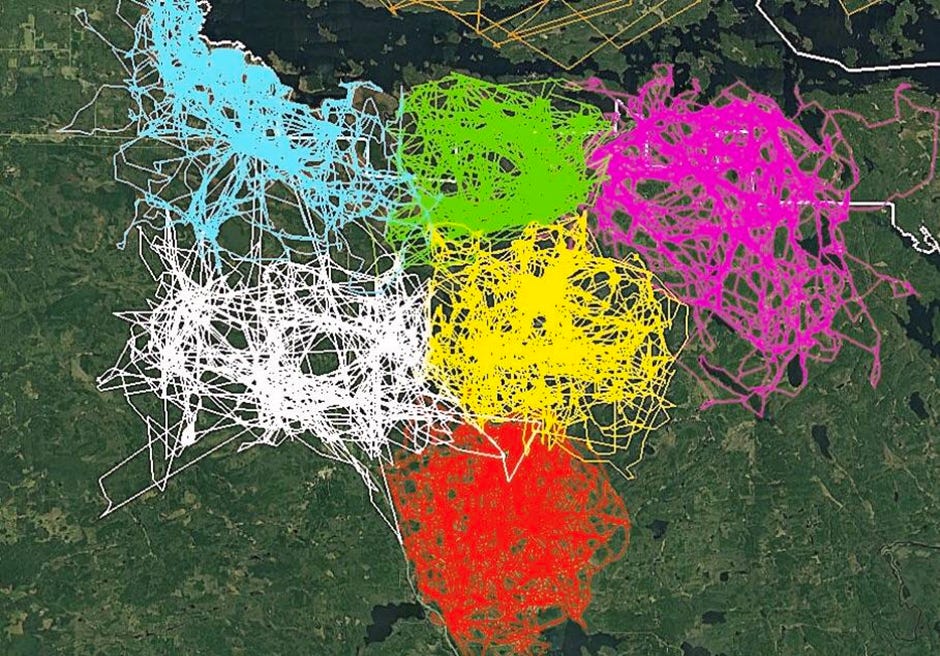

Here’s a map tracking the movements of six wolf packs that illustrates how hemmed in they are by each other.

Membership in a group, and the success of your group in war, means everything to hunter-gatherers. You can pursue personal accomplishment and status all you want, but if you’re part of a weak group your inevitable fate is extinction (if you’re male).

And this world is fantastic, it’s the best time in human history. Never again will people be happier than they were as hunter-gatherers. But from here onwards Moloch’s strength will only grow.

Hunter-gathering is a means of substance that requires a huge area of land.

Most wild plants that grow in your territory won’t be edible, most animals won’t be easy enough to catch, or are too small for it to be worthwhile, or they get eaten by other predators.

The maximum size of a group’s territory is limited by the area they can patrol (or maybe communicate across, or monitor for freeriding etc.) to exclude outsiders, and that area of land won’t support many hunter-gatherers.

Richer lands might support more people, but HG group size is constrained by this limit on territory size (you can do rough calculations that give an answer close to Dunbar’s number), they are larger than chimp troupes but still fairly small, rarely above 250 people.

What hunter-gathering does get you is an easy life. You’re just collecting what nature provides, and the work you do have to do is stuff your ancestors have done for millennia, so natural selection has given you an appetite for it, people enjoy doing things like hunting or hiking. (I’ll do another post about why HGing is so gratifying.)

Hunter-Gathering requires lots of land but doesn’t require much labour.

Archaeologists have noted that hunter-gatherers were taller and healthier than the farmers that replaced them. So it’s a puzzle why hunter-gatherers would adopt farming if it made their lives worse.

Farming is the opposite of hunter-gathering in ecological terms, by only growing edible plants on land you can increase the number of calories it produces (available to humans) enormously.

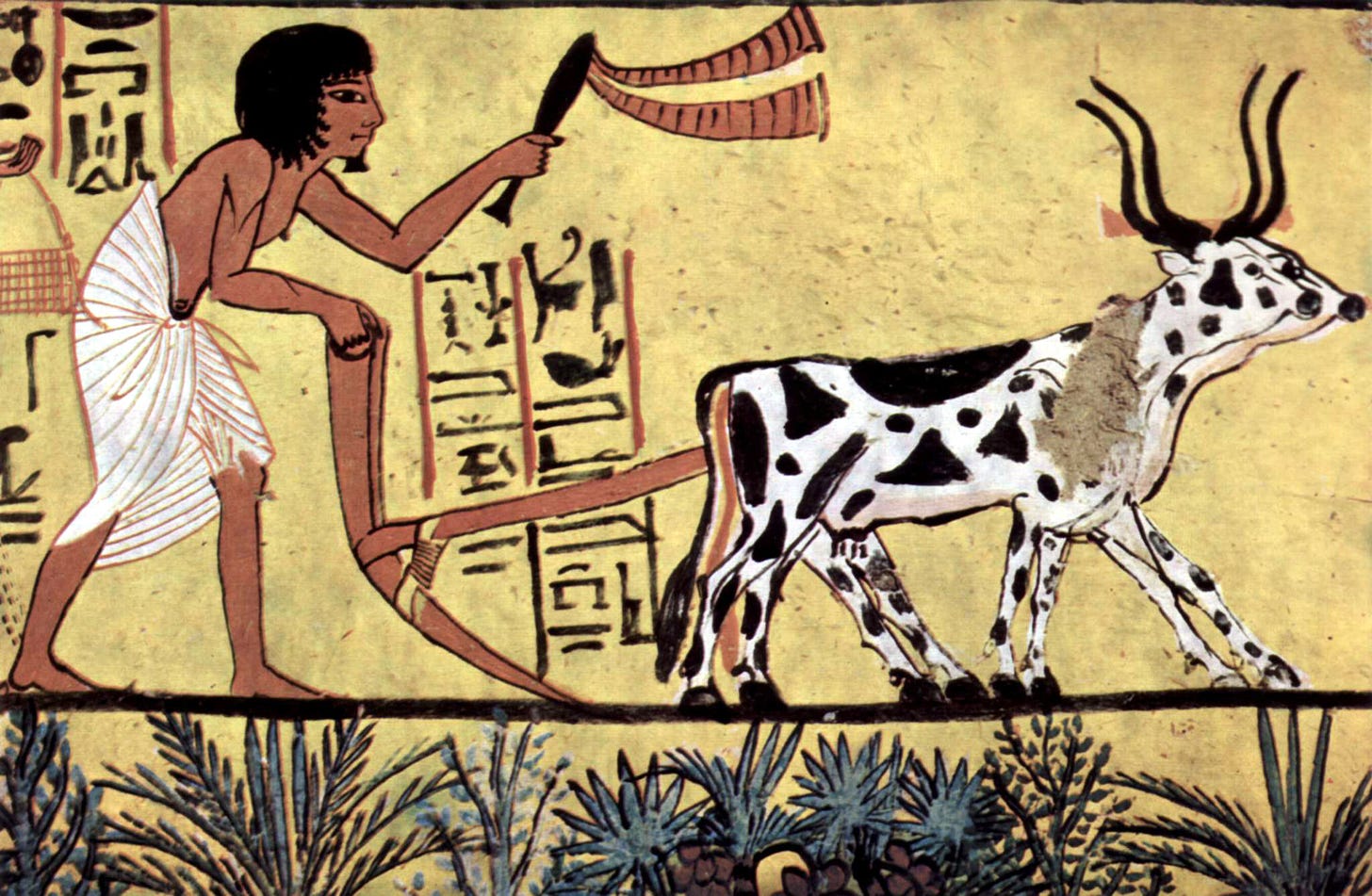

But growing plants, rather than just collecting them, or hunting an animal that’s essentially collected plants for you, requires a huge amount of work, and not the fun kind of work. It’s hard labour that human bodies aren’t adapted to. Grovelling in the dirt with digging sticks and stone sickles. Spinning and weaving thousands of threads by hand.

All for a bland, monotonous diet, and a lifestyle that barely keeps you clothed and housed. Early farmers had worn-out, stunted, skeletons from the toil and poor nutrition.

Farming requires lots of labour but doesn’t require much land.

There’s something called the “Sapient Paradox” which asks "why there was such a long gap between emergence of genetically and anatomically modern humans (~300k years ago) and the development of farming and complex societies (~10k years ago)?"

And the reason is that primitive farming is miserable, you really don’t want to rely on it unless you absolutely have to. Imagine being a mediaeval peasant, but with worse technology and un-domesticated crops that have yields so low they barely keep you alive, even if you cultivate land 16 hours a day.

What could have forced hunter-gatherers to adopt farming, if it was so dreadful?

A shortage of land, because rival groups were competing for all the nice places to live.

The end of the ice age changes which parts of the world are habitable, the Sahara used to be lush grass lands but dried up about 10,000 years ago, everywhere around the newly inhospitable areas is going to suffer an overpopulation crisis from refugees, and competition for land will become even more intense than the normal population growth usually sustains.

Any group losing this competition will face a stark choice: either risk annihilation fighting stronger adversaries, starve, or find a way to produce more food with less land.

Agriculture supports much larger group sizes, essentially unlimited, there’s more food per unit area of land and there’s no need for patrols if your whole territory is always populated.

In a contest between farmers and hunters, the farmers may be stunted and malnourished but there’re hundreds of them, the hunters stand no chance. Once one group adopts agriculture other groups need to follow or face the fate of the Tasmanians. Which leads to the inexorable spread of farming and extinction of hunter-gathering.

Violent competition replaced a world of leisure, scarce wants, relative equality and natural contentment (admittedly all payed for in human lives) with one of chronic scarcity, dehumanising labour and, as we’ll see, a society based on coercive domination.

In their desperation, by growing plants those early farmers made an awful Faustian pact. A pact that doomed all humanity to a truly wretched existence for many millennia to come, but hopefully also one that has set us on the path to salvation. Our original sin.

Farming may have enabled peace within large groups of people, and offered an escape from the ancient Malthusian pressures and the world’s natural carrying capacity, but, as it metastasised through the Garden of Eden, it also shocked humanity out of the ecological niche we’re adapted to live in, and ignited a population explosion that may never equalise and that still threatens the stability of the Earth’s very life supporting systems.

The respite from Moloch that farming provided could only ever be temporary however, because if the population isn’t controlled through violence it will be controlled by famine or disease.

[In part 2 (the final part), I’ll cover the spread of farming around the world, the earliest states and the return of Malthusian conditions to the pre-industrial world. As well as why I think this interpretation of human history should matter a lot to us even in the modern world.]