Economic Calculation in the RTS Commonwealth

Analysing the economy in Age of Empires and whether it suggests Soviet central planning could have worked.

Planned economies are notoriously less efficient than market economies.

In the early and mid 20th-Century, planning was widely accepted as the logical next step in economic organisation, in the East and the West. But since the disappointing performance of planned economies from roughly the 70s onwards, and particularly since the outright collapse of the USSR, the economic consensus has decidedly turned away from planning.

Soviet planning, along with the Cuban, the Maoist Chinese and North Korean economies, were interesting experiments, but ultimately only demonstrate the infeasibility of planned economies in the modern world.

And really, the Soviets should have realised that their vision for the world economy was always a lost cause from the start.

Theoretical works outlining the kinds of problems that the USSR encountered date back a long way. Ludwig von Misses demonstrated the impossibility of knowing what to produce, and organising production effectively, without markets, in his Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth in 1920, 71 years before 1991, an argument that became known as the calculation problem.

WHAT IS THE CALCUALTION PROBLEM?

[This section is just for background info, feel free to skip if you already know about economic calculation or just want to see my main argument.]

Misses’ argument was that production chains in modern economies are extremely complex.

To make just one pencil, for example, you need wood for the body, graphite for the lead and a machine for working those materials (some kind of lathe?). And to get the wood you need chainsaws, timber trucks, sawmills etc. Which, in turn, need to be made from steel and fashioned on [maybe a lathe again?], and the truck tyres need rubber, and so on.

Equally, the graphite needs to be mined and transported using [mining equipment] and [transportation equipment], which are assembled from [mining and transportation equipment components] made using [probably also lathes]. And the pencil lathes needs components from a [pencil-lathe lathe, possibly].

What’s called the economic calculation problem.

Every time you want to make one thing, you have to also make its inputs, and those inputs have their own inputs, which have their own inputs, etc. etc. In a branching tree of inputs that grows exponentially until you reach raw labour and natural resources at the bottom.

Most people in their everyday work only do specialised labour at one point on an input tree, Adam Smith’s famous division of labour, so aren’t usually confronted by the problem of figuring out how to make the thing they need to make the thing that’s needed to make the ting that they’re meant to be making. They just ask someone else to supply them with stuff from one level down the tree.

But even so, on it’s own figuring that out isn’t a huge challenge in principle (although, clearly I couldn’t for the pencil example.).

You could probably have one guy who knows every step in producing pencils and wood and graphite and lathes etc., for most industries, I would have thought. And, in principle that guy would be able to organise the making of pencils.

What makes calculation a USSR-collapsing problem is knowing what proportions to make things in, and knowing how much making one thing reduces you capacity to make other things, the opportunity costs.

If one pencil needs 10 grams of wood and 5 grams of graphite, i.e. a 2:1 ratio, and your pencil making operation outputs wood and graphite in a 1:1 ratio, half your graphite is going to waste. And half the inputs for you graphite also ultimately get wasted. If input-1 for graphite is also made inefficiently, and input-17 for input-1 for graphite is also being made inefficiently, those inefficiencies compound on each other and can amount to a massive overall inefficiency.

Naturally you can use the spare graphite for something else, but then you need to organise another production tree and try to get those inputs in the right ratios, often you’ll end up with a big pile of graphite no none has any use for. Also, you’re producing something that, presumably, you want less than pencils, so it’s still entails inefficiency.

And, in addition to that problem, you also need some way of comparing the relative values of those inputs so you can know what you could be producing instead of pencils.

Hypothetically, say that the raw labour, capital and natural resources, at the base of the pencil input-tree, could produce a house, if fed through a different input-tree. Then, by choosing to make a pencil you’re effectively choosing not to make a house instead.

But unless you have some way of measuring all the raw labour, capital and natural resources that ultimately end up in a pencil, via all its inputs and the inputs of those inputs etc., you won’t know that the resources being expended on one pencil could have produced a house, and you’ll waste resources that could have produced something much more useful.

You have no way of knowing what the opportunity cost is.

And, it’s also impossible to know whether the input tree you’re using is the most efficient one, or if it’s even roughly efficient. Maybe there’s a way to make pencils that doesn’t involve several tones of brick and roofing tiles. If you can’t calculate opportunity costs there’s no way to know.

Misses argued that in market economies this calculation is done through money. More specifically, “price signals”.

At each level of the input tree the producer buys input from the level below and sells outputs to the level above, ending in the finalised consumer goods.

The price a producer is prepared to pay for inputs (or the consumer is willing to pay for the final product) reflects the usefulness (or subjective utility, if you want) of that input, and insures inputs aren’t expended on wasteful processes, or directed toward making things that people don’t want enough to justify the production costs.

Likewise, the price a producer is willing to sell his output at reflects the cost he endured making it, including all the summed costs from further down the input-tree (which he paid for).

This way, market economies have an inbuilt mechanism that ensures that 2 tons of graphite don’t get produced if there’s only a justifiable use for 1 ton. Because the guy buying graphite to make pencils won’t be prepared to pay money for excess graphite. If 2 tons of graphite do end being produced, the price of graphite drops (a signal to produce less) and pushes the least profitable (i.e. the least efficient) graphite producers out of business.

Equally, market economies are virtually guaranteed not to produce pencils if they could produce houses for the same inputs, because the final consumer won’t pay the price of a house for one pencil. A business producing pencils that inefficiently will have huge input costs and tiny revenues.

This ability of market economies to calculate rational prices really is kind of miraculous, and the modern industrial economy wouldn’t be possible without it.

[This is a fairly brief overview of Misses model of calculation, see David Friedman’s Price Theory for more detail.]

Misses goes on to argue that you can’t have meaningful price signals without private property, essentially because people won’t mind over paying for stuff if it’s not their money, and therefore that for socialist economies it’s impossible to organise production rationally.

When central planning-offices try to run national economies they necessarily end up producing pencils instead of houses and waste half the graphite, in every sector of production.

“[A]s soon as one gives up the conception of a freely established monetary price for goods of a higher order, rational production becomes completely impossible. Every step that takes us away from private ownership of the means of production and from the use of money also takes us away from rational economics.”

“Without economic calculation there can be no economy. Hence, in a socialist state wherein the pursuit of economic calculation is impossible, there can be—in our sense of the term—no economy whatsoever.”

“[H]e who expects a rational economic system from socialism will be forced to re-examine his views.”

And taking the Soviet economy as a (somewhat sorry) example of economic planning, it does appear that Misses was right. You can read plenty of accounts of soviet planners ordering pig sheds be constructed from concrete in heavily forested areas where wood would have been free, Soviet factories running at half capacity for want of supplies and equipment, etc. etc.

Calculation was one of several major problems for Soviet planners.

WHY MISSES MUST BE WRONG

But, reading Misses’ strong claims about how the “pursuit of economic calculation is impossible” and that there can be “no economy whatsoever” under socialism. I can’t help wondering:

Did this guy never play Age of Empires?

Admittedly, given that Misses died in 1973 he probably didn’t.

Still, I’m really struggling to imagine what Misses’ reaction would have been if he’d seen 10 year old me commanding villagers to collect wood in order to build a lumber camp, mill, barracks and archery range, in a specific sequences that minimises redundancy, directing them to gather food from berry bushes and the boar, then to gather from farms (arranged in the optimal pattern around a mill) when the high yield sources ran out. Ordering a mining camp be built to collect gold to pay unit creation costs. All whilst insuring constant minimum, but not redundant, food income, which depends on a multi-level input tree, to avoid any downtime in the town centre’s villager production. Ultimately leading up to a successful Feudal-Age archer rush against the hard AI on Gold Rush.

The core gameplay of Age of Empires, or any Real-Time-Strategy game: assigning tasks to workers, organising the layout of buildings, deciding which resources to collect when, and feeding those resources through production chains to produce a final output, is clearly an example of economic planning.

I was never an amazing AoE player, but even so, I can still organise the in-game economy in a way that’s reasonably efficient.

Based on Misses’ conception of economic rationality, it seems like that should be impossible.

[Misses was writing in the 1920s, before the development of the kind of modern information theory we use to discuss this issue nowadays, he just speaks in a less precise vernacular, so it’s not always completely clear exactly what he’s claiming.

Sometimes it seems like he’s saying “planning is just very inefficient” and sometimes “it’s almost impossible for planning to produce anything”. As far as I know, he never gave any kind of numerical estimate of how efficient planning could be in theory, the “no economy whatsoever” and “economic planning is impossible” quotes, sound like he’s claiming 0% efficiency to me.]

Maybe if Misses was confronted with a competent AoE player he’d respond something like:

“AoE economies have 200 villagers max and the production process are never more than a handful of steps long. So yes, it’s possible to plan a small, simple economy like this, but a market system would still outperform even the best AoE player. ”

I would be interested play against an AI opponent (?) based around a market system, where each unit acted independently, following their own interests without any centralised guidance. But I expect even a casual player would absolutely crush it. No contest.

Laying aside the fact that AoE games revolve around defeating an opponent militarily, and military force is a public-good which a pure market system wouldn’t provide. And the fact that new people are essentially created by the state in AoE. And the fact that AoE units have a utility function that looks like a graph of my life-time savings, they don’t need food after they’ve been created, or any other resources, and don’t have any wants, or any personal reasons to produce anything, if they’re not being mind-controlled, i.e. it’s completely flat.

I still think the quality of economic calculation a market system could achieve in this situation would be much worse than the best AoE players achieve planning their economies directly. For a few reasons:

1.) Some work that would normally be done by the player would need to be done by villagers:

Without a central planner deciding which tasks to do when and by who, as well as giving those orders, villagers need to spend time meeting up and bargaining with each other to produce the price signals they rely on for organisation.

Every time a new building needs to be constructed, villagers need to gather together and bid for the building rights on that piece of land. That bidding process does ensure the land gets put to the most profitable use, but it’s a costly process in of its self. A similar process needs to happen for the wood and stone used as construction supplies.

A market-based AoE economy also needs a bunch of infrastructure to facilitate the market transactions, which aren’t necessary if the player just plans things.

Some portion of gold that could be invested immediately needs to be withheld from productive uses to act as currency. (Although it’s pretty weird that AoE economies need gold at all since it’s not good for much beside currency.)

You need to build banks for investment, courts to enforce contracts, maybe a tax office, all employing villagers.

Overall villagers spend less time actually producing or constructing directly useful stuff.

2.) There’s no overarching base design:

Placing buildings in AoE incurs opportunity costs which would get neglected as externalities in a market system. Every building you place blocks anything else from being built there, and different types of building should be clustered together in a specific place relative to other buildings, in a way that probably wouldn’t be profit maximising.

You want houses clustered in a line as a preliminary, early-game defence, unit producing buildings and gold mines protected at the back, and sometimes everything to be enclosed by an outer wall.

If each villager just builds their house where it’s most convenient, or a villager-capitalist places their gold mine where a part of the wall should go, the defensiveness of the base as a whole gets compromised.

3.) There’s no industrial policy.

Most units and buildings in AoE require inputs of several kinds of resources, and the late-game units need special buildings and particular technologies to be unlocked from the tech-tree.

Typically, AoE players organise large parts of their economies and tech research around unlocking and having the resources for one or two particular units, in anticipation of spamming those units later in the game.

Price signals work like a gradient ascent function. They can’t act with any foresight, if the nearest peak isn’t the tallest peak they can’t climb as high as a planner could.

If villager-capitalist A happens to invests in producing wood, following short term profits, and villager-capitalist B invests in producing stone. But the only viable late-game units cost either wood and gold, or stone and food, they can’t cooperate to produce anything.

The same problem happens if competing interest just pick whatever techs are most useful right now and don’t bee-line down the tech-tree for a specific late game-tech.

Price signal are really bad at providing organisation across time.

4.) Price signals are worse the further an economy is from equilibrium.

If an economy is under-producing food, food prices will be high and incentives will point towards expanding food production. But if food prices are high because the last harvest happened to be bad and actually food production capacity is already sufficient that prices will be normal next year, it’s a mistake to invest in extra capacity, even if the current prices imply you should.

Prices lag real developments in the economy, sometimes by a long time, if the response to those prices has a significant start up time, like sowing crops for next year’s harvest, for example.

AoE economies grow extremely rapidly, I’d say they roughly double in size every five minutes. Prices are likely to be out of equilibrium fairly often.

If price signals are telling you to produce more wood, but 30 seconds ago a new lumber mill came online, and that new information hasn’t percolated down through the market transactions into prices, the information from price signals could be useless.

Which won’t be a problem for planners, they’ll know about new developments in the economy instantaneously (since they planned them).

And if you ever needed to abandon your base and move somewhere else, it’ll take a long time for price signals to percolate through the new restructured and out of equilibrium system. The initial organisation will be inefficient and will only improve slowly and incrementally. ( This is probably the main advantage in planning that let the Soviets industrialise to rapidly in the 30s.)

5.) Unemployment.

Market economies can suffer from structural unemployment because [insert some stuff about aggregate demand or crises of overproduction or whatever].

Some of the villagers might end up not doing anything at all.

Like I said, I would be extremely interested in seeing a market-based AI play AoE, but I can’t see it lasting five minute’s vs a decent human player/planner.

Which is interesting, because it demonstrates that there are at least some situations, if only quite niche ones, where planning can outperform markets.

THERE ARE LOADS OF SITUATIONS WHERE PLANNING OUTPREFORMS MARKETS.

Looking around you can actually find many real-life instances of planning outperforming markets.

Healthcare usually makes up around 10% of developed economies by GDP, and in many European economies the entire sector is managed effectively through a state planning bureaucracy.

Countries like Germany have more somewhat more decentralised systems, but in the UK the NHS is one giant organisation dictating how many hospitals to build and where, managing thousands of doctors and nurses, deciding which procedures to offer. (Admittedly, and since Blair especially, the NHS does have some market interactions with suppliers etc. I have to pay a nominal fee to pick up prescriptions for example. But it’s fair to say that the NHS is effectively planning a significant section of the UK economy.)

I’m the last person to suggest NHS runs with perfect efficiency. (I mean… they make me fill out a formal request for prescriptions every month) But it’s hard not to agree that the NHS runs about as well as the more market oriented American healthcare system, at least. Healthcare spending per capita in the UK is about 1/4th of US spending, and life-expectancies are actually slightly higher.

You could argue that isn’t a fair comparison since the US system isn’t a perfectly free market system, there’s still some government intervention. I’m not sure any modern developed country has been brave enough to attempt a completely unregulated system, maybe it would outperform systems like the NHS and it’s only mixed market-government system like the one in the US that are so dysfunctional.

But comparing a mostly planned system to a mostly price-signal based system, it looks like the NHS has achieved what the Soviets couldn’t.

Incidentally if you’ve read my Bullshit Jobs essay, I suspect the main inefficiency is that the US system employs huge numbers of changers.

War Planning. During the world wars countries engaged in the war implemented significant planning of their economies directed towards war goals. So, if price signals were directing a factory towards producing washing machines or some other consumer goods, the state would step in and command them to produce something like tanks instead, and they’d also direct the flow of resources to enable that as well.

One of the pioneers of the theory behind central planning, Otto Neurath, was the planning minister for Austria during WW1.

War economies have different goals to peace time economies, so maybe it’s not a fair comparison, but many national economies, the US in particular, grew rapidly during wartime.

The internals of corporations. Firms in market economies have market-based relations between each other, but organisation within firms is done through direct command, not price signals. i.e. you’re boss tells you exactly what to do by command, he doesn’t advertise each specific task and offer £2.50 for someone to fill out one spreadsheet, x1000 little jobs.

A book called The People’s Republic of Walmart documents how some very large firms, the eponymous Walmart and businesses like Amazon for example, that are comparable to small national economies in terms of value-creation, employ planning algorithms that are like more sophisticated versions of Soviet planning models.

The book also mentions a competitor to Walmart, Sears, was owned by a follower of Ayn Rand who attempted to introduce market mechanism into the internals of the firm, the opposite approach to Walmart. Effectively turning subdivision of the company into independent, competing entities, buying and selling services from each other. I don’t know if Sear is still a large presence in the US, think I’ve vaguely heard of it, but it certainly seems to be less prominent than Walmart.

Overall, it’s undeniable that under certain circumstances planning can work, and is sometimes even superior to markets.

That shouldn’t be surprising though, as Misses pointed out, it is true that there are inherent inefficiencies to central planning, but it’s also true that markets suffer from inherent structural problems as well. I listed what I think are a some of the main ones in the AoE example, transaction costs, market failures, blind gradient ascents, dis-equilibriums, and there’s a whole class of potential macro-economic problems pointed out by people like Marx and Keynes.

In some situation the inherent problems of planning will outweigh the inherent problems of markets, and vice versa.

But the question of “exactly when and where is it better to plan than to rely on markets” is a weirdly understudied area of economics. It seems like it could have fairly major practical implications, and it’s interesting from a historical perspective at least.

Exactly when is it Better to Plan than to Rely on Markets?

Republic of Walmart argues that planning is better for small firms/countries/organisation/RTS game economies, measuring size by GDP, and that planning gets worse, whilst markets get better (or at least don’t lose efficiency) the higher the GDP.

Which seems intuitive since the calculation problem get exponentially more complex the bigger an economy is, making it harder for a planer to calculate effectively. Whereas, for markets the number of actors (buyers and sellers) calculating price-signal grows proportionately to the size of the market.

They also suggest that since Amazon and Walmart are comparable in size to a small country in terms of GDP, and those companies manage to plan effectively, therefore planning should be possible at small national scales at least.

The idea that planning is usually superior at low levels of GDP and markets are superior at higher levels of GDP, with a crossover point somewhere around the level of a small country, seems roughly true to me.

But I can think of hypothetical scenarios where it doesn’t hold.

As a down to earth example, imagine a giant mining a huge diamond in the sky, and on the ground there’s just a normal human market economy. Say the mined diamond is extremely valuable such that the giant’s output makes up 90% of the value created in the country. By gdp, the giant mining operation is gigantic, it’s most of the economy, but planning the giant mining operation is extremely simple, in RTS terms you just right click the giant, let click the giant diamond.

Someone measuring economic systems by gdp would say that this is evidence that planning can function for really big systems. But in reality even though the giant mining operation is big in terms of value creation, that large GDP doesn’t correspond to much economic complexity.

Even scaling up the system doesn’t add much complexity. If there were 10,000 giants, the planners at Giant Mining Co. could write a script:

for( i=0, i<NumGiants, i++ )

{

LeftClick( Giants[i] );

RightClick( Diamonds[i] );

};

That could organise an infinitely large giant mining operation, with enough compute.

The authors of Republic of Walmart would describe this country as 90% planned, but it’s clear that some kind of measure of complexity should also factor in, as well. Measured by by complexity this country is 99.9999% market orientated (all the human activity on the ground).

So there are a few different ways to quantify what proportion of economy is planned, and I think this example also demonstrates that some industries are easier to plan than others.

The Soviet economy is usually regarded as being mostly planned, and by GDP it was. But by and large, Soviet planning was restricted to large, standardised, high-proportion-of-GDP sections of the economy, like oil extraction and steel production etc.

Measured by complexity, most of the Soviet economy was organised around (heavily regulated and publicly owned) market firms coordinating their activity through a circulating money supply. All the small batch items and dense supply chains, like tooth brushes, clothes etc.

[Incidentally, it was a break down of this part of the economy that caused the final crisis that toppled the USSR, when the state couldn’t raise enough tax revenue from the semi-private sector, largely because of the loss of tax from vodka after attempting to tackle alcoholism, and resorted to debasing the currency leading to an inflationary crisis, although of course there were also deeper problems. If you view taxes as the sates claim on a portion of national product, obviously this kind of of crisis couldn’t occur in a fully planned system where the state is entitled to anything and everything.]

In that sense, on a spectrum from 100% planned economy to 100% free market, we shouldn’t view the USSR as being not that far to the left of Britain’s social-democratic economy at the time, or modern China, probably roughly in the middle-left.

Considering complexity and size, I think we can get a metric that roughly indicates whether markets or planning will work better. (The dividing line should be curved really.)

And from here, an interesting question to ask is: are there parts of our 21st century Western economies that we don’t currently plan but that we should?

Should we be doing more planning?

As mentioned, healthcare is usually planned to some extent in developed countries and seem to operate better under that system than under a market system.

One sector that strikes me as especially difficult to plan would be agriculture.

Farming is strongly context dependent. Which crops will grow well varies from one field to the neighbouring field, and from one year to the next, depending on weather and soil conditions. Each individual crop can suffer from fairly unique problems, like specific deceases, pests, physical damage etc., which need to be addressed on an individual basis.

There’s no standardised blueprint that works well for every farm, or even a small number of farms in the same area.

Farmers are also keenly attentive to market prices for the crops they produce, and the prices of the inputs to those crops, like fertilisers, diesel for vehicles, seed prices etc. and they a typical farmer’s yearly schedule for his farm is heavily influenced by those price signals. If you work in the internals of a large corporation the only price signal you’re likely to routinely encounter is your own wage, whereas farms are often run by a single individual with direct connections to market forces both in what he buys and what he sells.

Overall, modern farms make extensive use of local knowledge and price signals, and run extremely efficiently as a result.

If you got the top AoE2 player, the Viper, to run one farm, I’d expect him to do an exceptional job. If you asked him to run the whole of national agriculture, even with a bureaucracy and a super computer, I’d expect him to do… well, better than most real world planners, but probably still worse than the market.

Also, as a broad claim, there don’t seem to be any major market failures in modern agriculture, or at least fewer than the typical industry.

I’d argue farms should be viewed as the archetypical opposite of an industry that’s amenable to planning. You’d need an exceptionally competent planner to outperform the market here.

[Most of these arguments are less true for traditional peasant agriculture. So I’m reluctant to say Maoist and the early Soviets should have foreseen the issues they had organising farming, and there were other consideration than just short term efficiency at the time, but it’s notable that those issues did exist.]

The major candidate for an expansion of planning in my view is housing.

The housing market sucks. Both because the rent is too damn high and as an abstract entity for organising economic activity.

If the agricultural market is like a super-human AI whose only concerned with efficiency, the price signals for housing are the equivalent of a lazy, schizophrenic coke addict with a gambling problem.

The average house in the UK is 37 years old, which means the price signals that led to its construction happened nearly 4 decades ago. The size of the current housing stock largely reflects economic conditions from the mid 20th century, it’s fortunate that demand for housing essentially follows demographic trends and isn’t prone to wild swings, because there’s almost no chance price signals would be able track them.

Housing is also heavily financialized. To a significant extent the price of houses reflects the availability of mortgages more than real demand, and this also leaves prices extremely prone to bubbles, irrational exuberance and cyclical swings. And crashes in the housing market reverberate around the whole economy, or even the world economy as in 2008.

In terms of matching supply to demand, the housing market has an exceptionally easy job and is still a chronic failure. Its response to shifts in demand are glacial, lagging and largely speculative.

The useful information content in house prices is low.

On top of that, housing as an industry is absolutely riddled with market failures.

Construction comes with big externalities, placeing a building in one place obviously blocks all other possible building projects on that plot, and usually effects the value of all the surrounding plots.

Because of the permanence and construction time of houses, the incremental approach of market systems, with no overarching design, can’t function, or only iterates extremely slowly. Once you placed a building somewhere, you can’t revaluate if it would be better somewhere lese given the locations of all the new subsequent buildings you’ve placed. At least some central coordination is necessary. Left to itself the market would build a chaotic, overcrowded jumble of buildings.

Information asymmetries are also common. Buyers rarely have the expertise to know if a house is well constructed with quality materials. Routinely newly bought houses develop maintenance issues some time after the purchase.

Apart from the dysfunction of the housing market, housing also has some features that make it particularly suited to planning.

Constructing houses is the kind of rote, standardise-able process where localised information usually isn’t vital.

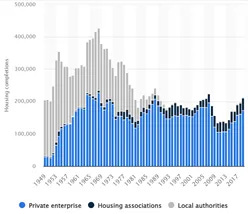

Because of the information asymmetries mentioned, the state is already heavily involved in regulating housing construction in most developed countries, ascribing building codes, monitoring the quality of construction materials, and of course issuing planning zones. The number of mortgages financed is also largely determined by central bank monetary policy. And many governments already have histories of large public construction projects. (For the UK:)

.

An expansion in state planning of housing would be an incremental reform.

[There’s a wide spread YIMBY argument that local planning regulations are responsible for strangeling the housing supply, which almost certainly is true, even if it’s not the main factor causing the current housing crisis. I don’t think this a strong argument against centralised planning as NIMBYism is almost always a product of local planning authorities, established interests in an area looking to preserve their own property values. It’s more an example of a failure of decentralised planning, which honestly barely counts as planning, a centralised planning office wouldn’t have incentives to behave that way.]

If there’s an element of the housing market that’s worth preserving, it does allow people to express their particular desires for where they’d like to live, people who prefer living in cities are free to bid for those locations, ditto for people who prefer the countryside or have particular preferences for schools or whatever. But it’s worth pointing out that these communal aspects of choosing where to live are collective action problems. I could foresee a mixed system servicing those want more effectively, but the main area with potential for improvement is in construction more than allocation.

Final Thoughts

I can’t help feeling mainstream economics has been too quick to discard planning as an economic tool. The calculation debate used to be a major feature of econ discourse, but questions like: When can planning be effective? What’s the most effective way to run a planning office? How does the efficiency of planning scale with size and complexity? Which sections of the economy would be easiest to plan, or the most difficult? are question contemporary economics doesn’t seem especially interested in.

In the interim between when planning lost much of its credibility in the mid 20th century and the year 2023, several major developments have taken place that plausibly could have affected the feasibility of planning.

Our computing power is vastly greater. In a sense the market economy is effectively a giant computer, but it’s a giant computer of a fixed size (relative to the economy as a whole), it’s not inconceivable that ever more powerful real computers could potentially out-compute it. Reading accounts of Soviet planning, it’s clear that at least a portion of their problems were due to a lack of compute. For much of Gosplan’s history, calculation was done on literal abacuses, which limited the scale and detail of plans enormously.

Our communications technology is vastly better. Centralising information has never been easier, whereas Soviet planners where limited to basic weekly production reports over a telephone line to a bureaucrat taking records on paper, electronic record keeping and the internet allows subunits in large corporations to report ongoings precisely, and coordinate between each other, in real time. An economy-wide version of a system like that would be well within our technological abilities.

AI strikes me as having absolutely staggering future potential for uses in planning. The technical process of running a plan comes down mapping the inputs and outputs for every industry in a giant matrix, then running a linear programming function to optimise the weights, a process that’s extremely similar to training a neural net. It would need to be area of technical research, but there’s the possibility of creating a kind of plan that’s itself a kind of AI mind. One that’s infinitely more adaptable and prescient than a typical fixed schedule plan. Integrating AIs directly into production processes would also huge expand the availability of information.

As we’ve seen, planning is usually superior for small systems. It’s not inconceivable that in in the not-that-distant future we’ll have AIs with so much compute, intelligence, access to information and that think so fast, that the whole national economy, or portions of it, is effectively as small system from their perspective.

China currently runs a much larger fraction of its economy directly though the state than is typical in the West, and seems to have had significant success, mostly in industries that this analyse suggests should be the least difficult, like petroleum, construction and railways, but also in areas that seem like they would be difficult, such as communications. China has also signalled an intention to move towards greater centralisation in its latest five year plan. And of course China has a history experimenting with planning.

RTS games where my first exposure to economics and a large part of what got me interested in it, I’m sure there are many people of roughly the same age in a similar position. I’m not sure how older economist typically were first exposed to economic ideas, I’m guessing just working and dealing with money as an individual in the real world, but role playing as a central planner must give you a certain set of intuitions about how economies work. And in general, I do find a lot of economics to be oddly centred around what’s happening with money rather than the real nuts and bolts of what’s actually being produced. Maybe there’s a new generation of economists that planning has an intuitive appeal to.

Overall, research into planning ought to feature more heavily in our economics in my view. I don’t view the historical experiments in planning that happened in poor, dysfunctional countries during the 20th century to be that informative to our current situation. Maybe we could get a small developed country like the Netherlands or Denmark to attempt wide scale plans, and the rest of the developed world could bail them out if they crossed the limits of what can work, since the results from the experiment would be useful to the world as a whole (only half joking here).

But if you’re still not convinced that central planning doesn’t deserve to be dismissed as casually as it often is, I’ve saved the most devastating argument till last.

Penrose:

I think the core conceit of this article works extremely well rhetorically. It’s attention-grabbing, funny, and thought-provoking. And I think your primary question of: “when do planned economies outperform market economies?” is interesting and worth exploring.

That said, the logic here didn’t work for me. I couldn’t quite tell if the AoE case study was meant to be tongue in cheek or not, but, assuming it was serious, I think there are some serious flaws in the reasoning.

First, Age of Empires doesn’t have an economy. It has a game system themed as an economy, and the underlying structure of the game system isn’t at all like the underlying structure of a country’s economy. The game system is an interesting optimization problem designed to be solved by a single person. There is a single meaningful output: victory in the game. Every piece of the system is an extremely crude abstraction meant to provide flavor to the underlying optimization problem.

An actual economy arguably has no single output to optimize for. It was not created and tuned by a small team of software developers, it is a word used to describe an emergent system.

Age of Empires is a toy optimization problem, not an economy, and the two are different enough that I don’t think you can discover anything meaningful by analyzing it as though it was.

As an analogy: imagine a jigsaw puzzle where each piece represented some discrete part of a country’s economy. When assembled, it created a pictorial representation of an economy. Presumably this would be easier to assemble in a “planned” fashion than by trying to create a model whereby pieces would fall into their correct place according to some algorithm. But this doesn’t tell us anything about economies.

A note about the US healthcare system:

I agree with you that healthcare is a mess in the United States, and would probably function better if it were more similar to the NHS. But it’s not really recognizable as a free market–it’s more of an oligopoly with some government price controls thrown in. Some specifics:

The majority of people get health insurance through their employer, which offers a subsidized plan. You can buy insurance on the free market, but its not subsidized, so it's vastly more expensive than whatever your employer offers. You don’t really have the ability to choose your insurance provider.

Then, when you go get healthcare, you can only go to certain “in network” providers. These providers won’t tell you how much your care will cost, even if you ask, so you can’t shop around and find a good deal. It’s also difficult to get information on care quality, so you’re effectively buying blind.

Medicare and Medicaid are about 40% of healthcare spending in the country, and they do have some price controls. IIRC hospitals lose money on medicare/medicaid patients, and then make up the difference by charging private insurance companies more.

Ironically, I think this market is pretty “efficient” in the sense that it makes people a lot of money, and charges exorbitant prices for something people hold dear. It’s just not efficient in the sense of equitably distributing care. Probably someone could rip apart the system and come up with free market version that worked much better, but at that point you may as well just go single payer.

Answering your specific questions:

Did the introduction drag on too long? I was thinking about cutting down the section on the calculation problem to stream line things, but I wasn't sure if it was necessary context.

I enjoyed the explanation of the calculation problem. I think you went into too much detail re: houses and pencils, but the core concept was good. I did sort of feel like you were strawmanning Misses in the following sections (surely he couldn’t have meant that planning is never useful for economic agents?), so making the case that he did mean that, or cutting the section entirely and relying on most people’s priors about planning being inefficient might’ve been a better tactic.

Is this just too broad a subject for a blog post to shift your priors?

No, but you’d need to provide a detailed real world example of central planning being effective, and I don’t feel you did that here.

Did any of the digressions feel pointless?

The giant diamond thing didn’t really make sense to me, and didn’t feel that important to your core argument. Also, the section on housing didn't feel rigorous enough to convince me that it would be better planned.

Just any thoughts or opinions people have on the topic.

I shared some above, but to close on a positive note: I thought the point about central planning being able to benefit from vastly improved computing power was interesting, and kind of exciting. The analogy of economy as neural net was thought-provoking. That point was probably what shifted my opinion the most about the benefits of planning.

> RTS games were my first exposure to economics and a large part of what got me interested in it, I’m sure there are many people of roughly the same age in a similar position.

It made me interested in being a dictator.

> AI strikes me as having absolutely staggering future potential for uses in planning. The technical process of running a plan comes down mapping the inputs and outputs for every industry in a giant matrix, then running a linear programming function to optimise the weights, a process that’s extremely similar to training a neural net.

Could you give me a specific example for the inputs and outputs? I haven’t actually put this on a whiteboard, but my gut tells me that supply chain management is a Traveling Salesman problem, which is NP-Hard. Of course, that means it’s NP-Hard for humans too. I bet that if you measure the complexity of the supply chain, as the complexity rises then the loss surface is going to become more and more non-convex, and then distributed approaches (ie market) economies will optimize it better. If the loss surface is smoother, then a central approach would be better. Again, just a gut feeling.

As for the intro, I would’ve liked to see a concrete example. We started with abstraction and then went to example, and I think this would’ve been more engaging the other way around. In “I, Pencil” the concrete example made something abstract feel very vivid. I want to see something at stake and that thing should seem like a matter of life and death. And this case it is. The Great Chinese Famine is considered one of the worst human-made disasters in history with some provinces losing 1 in 5 people to starvation. But America’s healthcare system is market based and enormously inefficient, and obviously lives are at stake there as well.